Shell Shock in World War I Literature

He stopped and looked across the field. The distance had vanished in a veil of rain. He didn’t know where he was going, or why, but he thought he ought to take shelter, and began to run clumsily along the brow of a hill towards a distance clump of trees. The mud dragged at him, he had to slow to a walk. Every step was a separate effort, hauling his mud-clogged boots out of the sucking earth. His mind was incapable of making comparisons, but his aching things remembered, and he listened for the whine of shells….

Something brushed against his cheek, and he raised his hand to push it away. His fingers touched slime, and he snatched them back. He turned and saw a dead mole, suspended, apparently, in the air, its black fur spiked with blood, its small pink hands folded on its chest.

Looking up, he saw that the tree he stood under was laden with dead animals. Bore them like fruit. A whole branch of moles in various stages of decay, a ferret, a weasel, three magpies, a fox, the fox hanging quite close, its lips curled back from bloodied teeth.

Chapter 4, Regeneration.

https://www.amazon.co.uk/regeneration-trilogy-pat-barker/dp/0141030933

I see a great blazing arc of flashes in the sky. At my right, a shadow scampers over the torn duckboards. A blackened face, huge eyes. He disappears. The ground has swallowed him….

I strain to clear my vision.

The shelling stops. My ears are ringing.

I hear a faint cry. A child’s whimpering?

I see it. A soldier has fallen into a shell-hole, filled with mud as thick as porridge, slimy and viscous like the starfish that fascinated me as a kid.

He is already submerged up to his shoulder.

Already? How much time has passed?

I break loose from my body, hover over the scene.

Is it really true that I crawl to the deep hole, murmuring some long forgotten song, and extend my hand?

A cry of agonizing fear.

Is it really true that everything on the front goes suddenly quiet?

I see myself extending my right arm, trying to pull the sinking soldier out of the mud.

Burbling at the corners of the mouth now.

I don’t have any power in my right arm.

I am too dazed.

The mud is as cold and clingy as the slush we used for snowballs, my childhood friend Leon and I.

I don’t have a grip on his body.

Am I pulling him by his hair now?

He’s gone.

The mud whispers: your fault, your fault…

Chapter Twenty-Seven, The Shadow of the Mole.

https://www.amazon.com/Shadow-Mole-Bob-Van-Laerhoven/dp/4824126436 (For this author’s book review, see: https://historicalnovelsociety.org/reviews/the-shadow-of-the-mole/)

Descriptions of shell shock appear as early as 490 BC when Herodotus tells of a soldier in the Battle of Marathon who was blind despite having no signs of physical injury. Shell shock was called Nostalgia in 1678 and Windage during the Civil War when otherwise healthy veterans of battle became weak and showed a “soldier’s” or an “irritable heart.” (Anthony Babington: Shell-Shock, A History of the Changing Attitudes to War Neurosis).

Shell shock became a widespread phenomenon among soldiers in WW I because of the nature of the conflict: trench warfare that kept soldiers in confined spaces while bombardments rained down and the dead bodies of their comrades lay next to them and exposed them to new types of lethal weapons—machine guns, artillery, gas and chemical attacks. (David Stevenson: Cataclysm; Austin Riede: Transatlantic Shell Shock)

Shell shock was first described as a medical condition by the physician Charles Myers in the British journal Lancet in 1915. Myers linked soldiers’ bouts of paralysis and the sudden inability to speak to “changes in atmosphere pressure under bombardment.” The condition was not considered to be a psychological response to combat experiences until the battle of the Somme, July-November, 1916, when casualties among British and French troops topped 600,000, (Cataclysm) and front-line physicians had little understanding of the condition, its symptoms and disabilities, nor clear ways to address it. (Transatlantic Shell Shock)

Novelists approached WWI shell shock in a variety of ways. Rebecca West and Virginia Woolf gave voice to women who observe the sequelae of shell shock in traumatized young men: the suicidal Septimus Smith in West’s Mrs. Dalloway (1925) and the amnesiac Chris Baldry in Woolf’s The Return of the Soldier (1918). Ralph Ellison and Toni Morrison illuminated the experiences of shell-shocked African Americans in Invisible Man (1952) and Sula (1973). Veterans recalled some of their own experiences in works of fiction: Richard Aldington in his story of the once outgoing painter George Winterbourne who withdraws from the world after the war in Death of a Hero (1929) and Siegfried Sassoon in the recollections of a fictionalized infantry officer in The Memoirs of George Sherston 1928-1936).

The two authors cited in this blog post introduce readers to men who are living with the effects of shell shock and the physicians who treat them.

Pat Barker, Regeneration

The first of the three novels in Pat Barker’s Regeneration series, was published in 1993. (The second, The Eye in the Door, followed soon after, and the third, The Ghost Road, appeared in 1995, winning that year’s Booker Prize.)

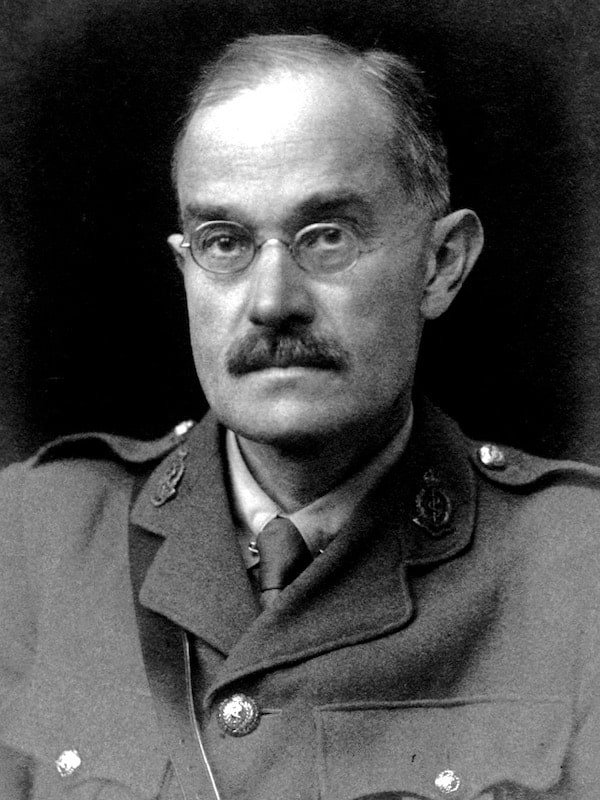

Regeneration tracks the paths of real life and fictional WW I veterans as they are being treated in Craigslockhart Hospital, Edinburgh, in 1917. The patients include writers Siegfried Sassoon and Wilfrid Owen, both known for their poems and other writings about shell shock, as well as the imaginary patients Prior and Burns. The novel centers on treatments and the physicians who administer them. In addition to the fictional Dr. Brock, Regeneration features W.H.R. Rivers, a neurologist, social anthropologist, and army captain, and Lewis Yealland and contrasts the two schools of thought about clinical interventions that would address shell shock and quickly return fighting men to the front.

https://litfl.com/william-halse-rivers/

Rivers led patients to explore their feelings, reconsider their notions of what it means to be a man, and recount their painful recollections of combat to restore emotional health. Barker relies on Rivers’ own descriptions of treatment methods: His report “The Repression of War Experience” was published in Lancet in 1918, and his book Conflict and Dream, which refers to Sassoon at “Patient B,” was published after his death in 1923. Yealland made use of external shock therapies, such as applying electrodes until a mute patient was able to speak again, and explained the techniques in his own book Hysterical Disorders of Warfare, published in 1918. (Regeneration Authors Note)

Bob van Laerhoven, The Shadow of the Mole

Finalist for the 2022 Best Thriller Book Award in the Historical Fiction category, The Shadow of the Mole also melds fiction with facts about the recognition and treatment of shell shock. Psychiatrist-in-training Michel Denis is working with a patient nicknamed the Mole, a man discovered by French sappers in a tunnel in the Argonne in 1916. The Mole has no recollection of his present or his past life and believes he himself has died and been replaced by the Other who presses him to write the Other’s complex history, a history that includes interactions with the physician and physiologist acknowledged by Sigmund Freud and others as the progenitor of psychoanalysis—Dr. Josef Breuer.

Breuer reported on the results of his treatment of a patient he had diagnosed with hysteria in 1880. The patient, identified as Anna O., was social worker and writer Bertha Pappenheim. Breuer was able to relieve Anna O.’s symptoms of neurosis by using hypnosis to guide her as she remembered the unpleasant experiences she had suppressed. Freud characterized Breuer’s case study as the impetus for his method of exploring the unconscious minds of patients and bringing to light the unconscious causes of their symptoms. (https://www.britannica.com/biography/Josef-Breuer)

http://www.ecured.cu/index.php/Josef_Breuer

Both Regeneration and The Shadow of the Mole highlight the lack of understanding of the widespread presence of shell shock in military veterans that existed not only during WW I but continued through WW II and other major conflicts. The phenomenon was not fully recognized until the 1980s when medical professionals and the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs labeled the condition post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD).

The next post in the Time Stamp blog will provide a brief history of the ways the recognition and treatment of shell shock evolved over the decades.

Sources

Austin Reade, Transatlantic Shell Shock, University of Georgia Press, 2019

David Stevenson, Cataclysm, The First World War as Political Tragedy, Basic Books, 2004

Pat Barker, Regeneration, Plume, 1991

Siegfried Sassoon, Memoirs of an Infantry Officer, Penguin Books, 1930

Rebecca West, The Return of the Soldier, Penguin Classics, 1918

Virginia Woolf, Mrs. Dalloway, Everyman’s Library, 1928

(https://www.britannica.com/biography/Josef-Breuer