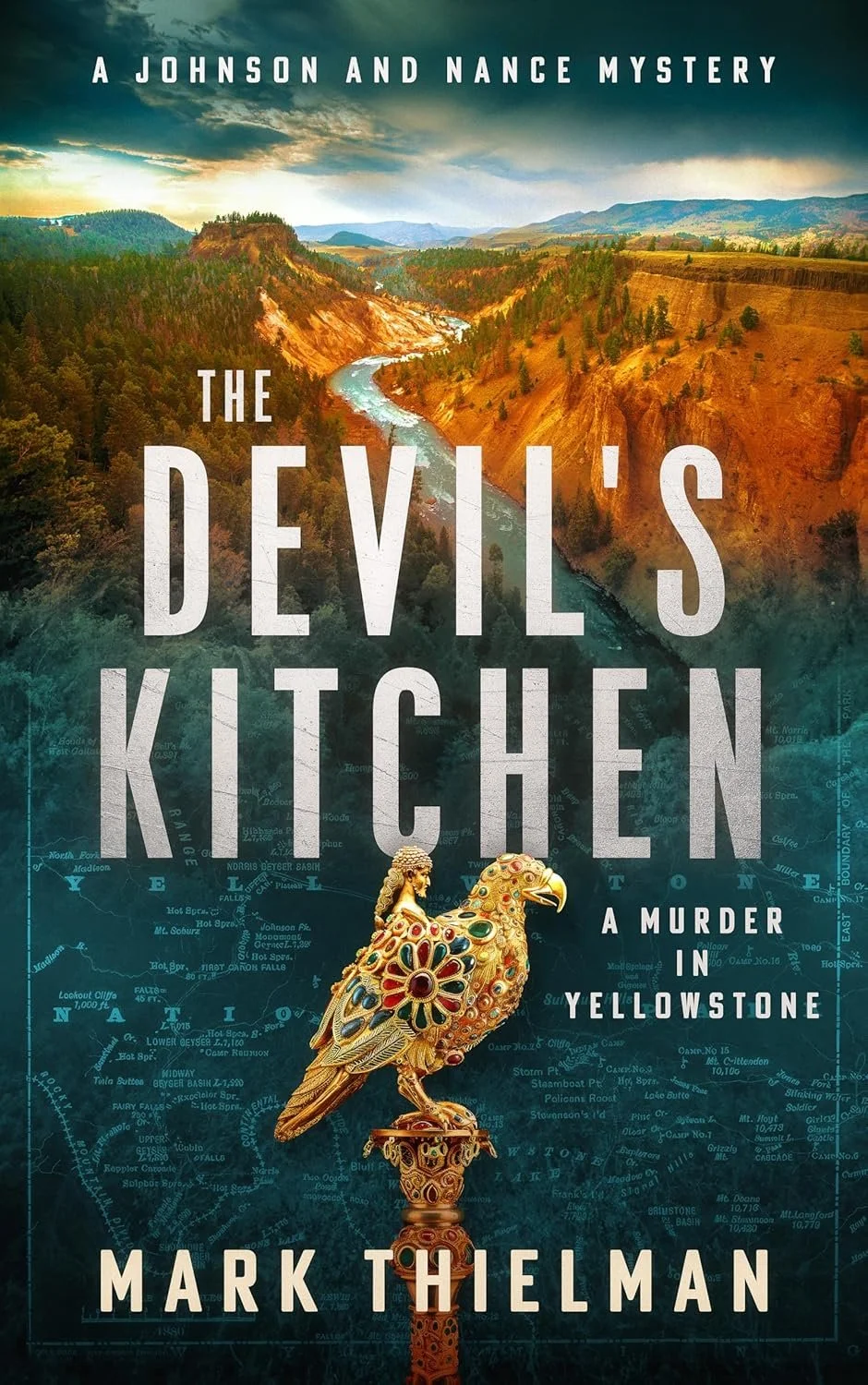

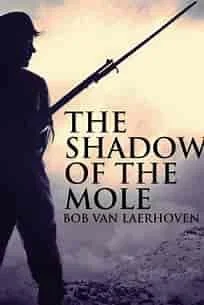

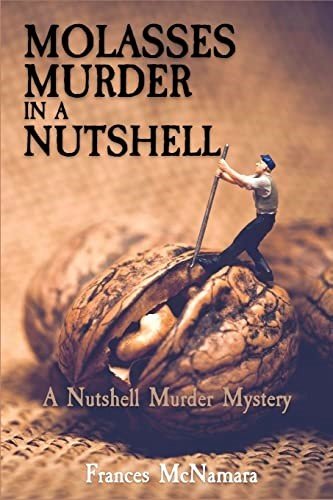

The Devil’s Kitchen--France

Artist Jacques-Louis David is sketching the serpent Ouroboros, its mouth tearing at its own tail. Apropos, he thinks, of France in its time of revolution, a time when the nation is feeding on itself. He is listening to his wife Charlotte talk about the “finger of god,” the oldest of the monarchy’s crown jewels, the relic that carries the force of St. Eligius’ touch.

And he recalls January, 1794, when he and Maximilien Robespierre watched a prisoner bound to a board that was lowered until it was horizontal, clicking as it passed each of the seams in the wood “like snapping teeth” and then heard the thud of the blade and the cheers of the crowd as a traitor to the Republic was brought to justice.

Robespierre worried at the time about the “relics of the failed regime,” the “jewels of a faded king.” They all must be found, he told David, especially the oldest of the crown jewels, the Scepter of Dagobert, the golden carved staff that was forged in the 7th Century and had been hidden by the Royalists. “We will find it,” he said. “We will turn over every hovel, every pigsty until this symbol of royal oppression is located.”

Charlotte now hints to David that she knows where the scepter is and then tells him about an audacious plot—the plan to secretly move the staff out of the country, first to Louisiana and then to the farthest corner of the American frontier, to Devil’s Land on the banks of the Yellow Rock River.

The Devil’s Kitchen tells of that plan, moving back and forth in time from late 1700s’ France to modern-day Yellowstone National Park where some are still looking for the Scepter of Dagobert. This blog post travels more than 200 years into the past and the days of the French Revolution. The next post slips back in time from 2025 to the early days of Yellowstone National Park.

The Scepter of Dagobert

The object at the center of intrigue in The Devil’s Kitchen, the Scepter of Dagobert, was one of the most iconic symbols of French royal authority and, as such, a target of artists, peasants, and Revolutionaries who sought to destroy monuments to France’s feudal past.

Made of enameled and filigreed gold, the scepter was 56 cm long, the rod was topped by a carved hand cupping a globe of the world, and at its apex, a dove.

The scepter was created during the reign of Dagobert I, a Merovingian king who consolidated Frankish lands and fostered devotion to the Christian faith during his ten-year reign—629 to 639. Used in official ceremonies, such as coronations, the scepter epitomized the power and authority of the king. It bore royal as well as religious significance, reflecting the divine right of kings, the belief that kings were appointed by god to rule and promote the spread of Christianity, and the melding of church and state.

In the late 1700s, the scepter was viewed as a relic from a time of oppression, a despised mark of the monarchy that was reviled by iconoclasts. It was only one of millions of objects targeted for destruction during the French Revolution when the iconoclasts set out to eliminate visual representations of the Catholic Church and the realms that came before the French Revolution—the Ancien Regime.

The French Revolution and the Iconoclasts

Although tensions were high as early as 1775, the start of the French Revolution was linked to the storming of the Bastille in July, 1789. In the next few years, feudalism (1789) and the nobility (1791) were abolished, the monarchy was overthrown (1792), and the king was executed (1793).

During this time, churches and monasteries as well as properties owned by the clergy and aristocracy were nationalized quickly and haphazardly. “Priests were removed from their property, monasteries were turned into stables for animals that shat in the space medieval altars once occupied, filth coated frescoes made centuries before, and crowds in the grips of a secular iconoclasm tore down and burned religious items.” (Thomas Lecaque: Revolutionary Material Culture Series)

Iconoclasts took specific action against “incarnations of the monarchy [that] obstructed man’s liberation.” (Frederique Baumgartner: Rethinking Revolutionary Vandalism in Iconoclasts and Vandals). In 1790, artists petitioned the king to order the destruction of all feudal monuments, and the National Assembly on June 19 passed the first iconoclast decree, which resulted in the partial dismantling of the statue of Louis XIV. Ironically, the commission for the protection of monuments was created in 1790, and the Museum of the Louvre opened on the first anniversary of the fall of the monarchy. Yet royal statues and monuments continued to be mutilated in what’s been called the Iconoclasm of Year II.

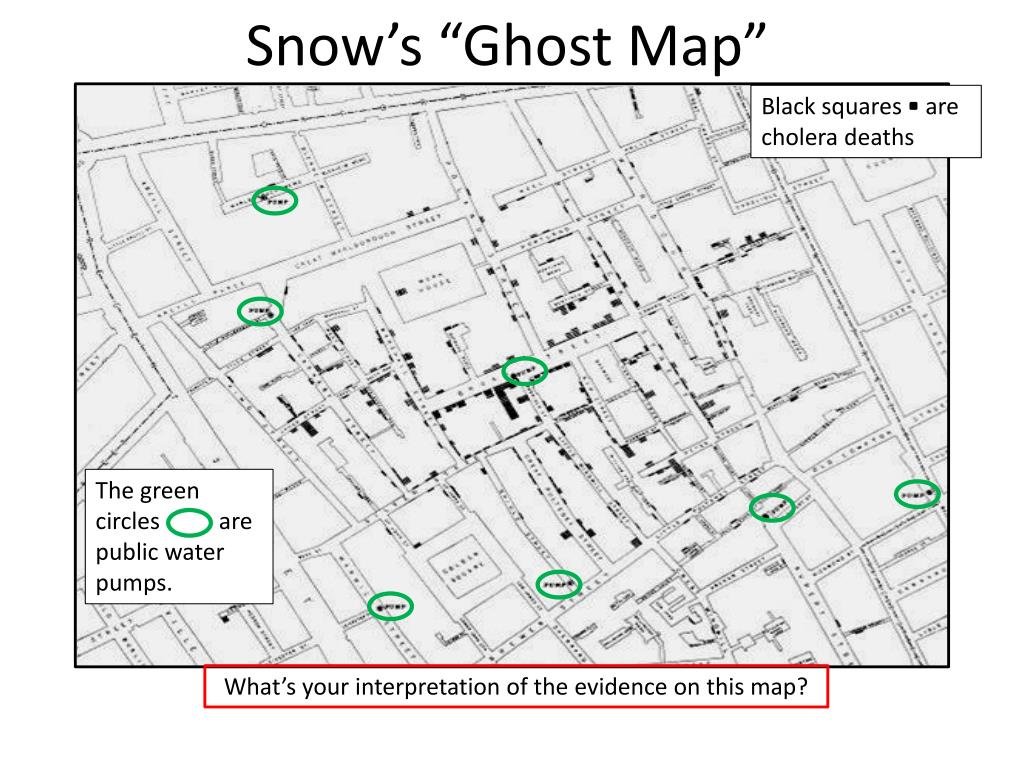

In 1792, peasants tore down feudal monuments on their own, prompting the legislature to pass a law that mandated such action and leading to the felling of the statue of Louis XIV in the Place des Victoires. In 1793, state-sponsored vandalism targeted Notre Dame Cathedral--statues mistakenly believed to be monuments to previous kings were decapitated, the treasury was ransacked, artifacts were looted, desecrated, or burnt--and the royal tombs in the Basilica of Saint-Denis were looted. (Iconoclasm during the French Revolution, Wikipedia)

Vandalism peaked during the Reign of Terror, from September 1793 to July 1794, when tens of thousands of people were massacred, publically executed, or died in prison as enemies of the new French Republic. Iconoclasm declined significantly in 1795, when the new government, called the Directory, instituted a nationwide plebiscite and granted amnesty to political prisoners. Iconoclastic practices ended in 1801 when Emperor Napoleon and the Catholic Church approved the Concordat, redefined the role of the church in the country, and outlawed the confiscation of church property.

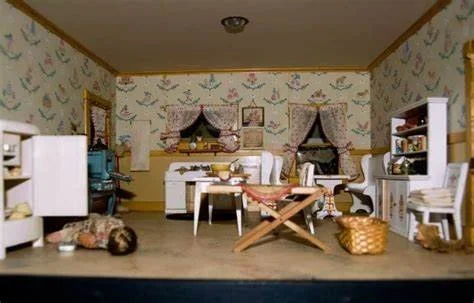

What Was Saved

Some monuments to the church and France’s historic past escaped the iconoclasts. Sculptures and other artistic materials were gathered in a former convent on the left bank of the Seine by Alexandre Lenoir. (Paintings were sent to the Louvre.)

https://collections.louvre.fr/en/ark:/53355/cl010066527

Labeled an “undistinguished painter” in 1790, Lenoir was named director of a depot of material obtained from religious institutions by the National Assembly and the mayor of Paris. As such, he “plunder[ed] before the plunderers, taking things apart before the mob did.” (Christopher M. Greene: Alexandre Lenoir and the Musée des monuments français during the French Revolution, French Historical Studies, Vol. 12, No. 2 (Autumn 1981), pp. 200–222, Duke University Press)

Lenoir helped protect works of art and history and was wounded at least once while trying to stop the corpse of Cardinal Richelieu from being mutilated in the Sorbonne chapel. “He didn’t succeed—soldiers displayed what remained of Richelieu’s head on a pike to the appreciative crowd—but he did eventually get the tomb itself transferred to the depot.” He also covered bronze statues with “grayish distemper” to disguise them as marble and prevent them from being melted down for bullets. (Greene)

What Was Lost

Manuscripts and written records prior to the French Revolution suffered the most losses by iconoclasts. One scholar estimated that more than four million volumes were taken away from monasteries and burned, including 25,000 medieval manuscripts. (Lecaque)

It was no wonder, he observed: “These documents were the legal justification of the privileged to rule over the peasantry and urban underclass, and when rebels burned them they were using similar intellectual justification to Tyler Durden’s [the character played by Brad Pitt and his] plot in [the 1999 film] Fight Club: a destruction of the debt and the control over their lives through a sudden, cataclysmic violence against the records. The Revolution was the greatest of these, though there were near-contemporary preambles in the south [of France]. In the 1780s, rioters in the Cevennes, Vivarais, and the Gévaudan all broke into law courts and the homes of notaries and attorneys and attempted to burn the deeds and contracts—a decade later, their attempts would be sanctioned by the revolutionary regime.” (Lecaque)

Major monuments also were destroyed. Among the most notable, Lecaque reported, were: “’The statue of Notre-Dame of Puy, which in early times attracted many foreigners, among whom were illustrious kings, and which considerably favored the economy of the town, was ripped from the main altar of the cathedral on the 30 Nivose of year II of the Republic (January 19 1794), and transported into the archives of the cathedral.” The famous ‘Black Madonna’ statue of the cathedral, was stripped of its jewels and left inside. The statue and the archives shared a similar fate: on June 8th, Pentecost of 1794, soldiers, police, the revolutionary head of the Haute-Loire, the mayor, and others took the statue and put it into a fire in front of the hôtel-de-ville, alongside ‘a quantity of papers called ‘feudals’ and others remembering ancient events. This operation was done to cries of ‘Long live the Republic!’” and forever eliminated the cathedral’s historical archives as well as its principal relic. (Lecaque)

As for the Scepter of Dagobert? It disappeared from the Basilica of Saint-Denis, the resting place for many French kings, in 1795.

Sources:

Christopher M. Greene: Alexandre Lenoir and the Musée des monuments français during the French Revolution, French Historical Studies, Vol. 12, No. 2 (Autumn 1981), pp. 200–222, Duke University Press

geofrevolutions.com/2019/04/29/archives-lost-the-french-revolution-and-the-destruction-of-medieval-french-manuscripts/

Thomas Lecaque: “Revolutionary Material Culture Series,” April 29, 2019.

Matthew Wills: Wikimedia Commons, June 1, 2024

https://www.britannica.com/event/French-Revolution/The-Directory-and-revolutionary-expansion

https://www.britannica.com/place/France/The-Napoleonic-era

https://www.britannica.com/event/Concordat-of-1801

Saving Art from the Revolution, for the Revolution: Alexandre Lenoir’s Musée des monuments français, founded to protect French artifacts from the revolutionary mobs, was one of the first popular museums of Europe.