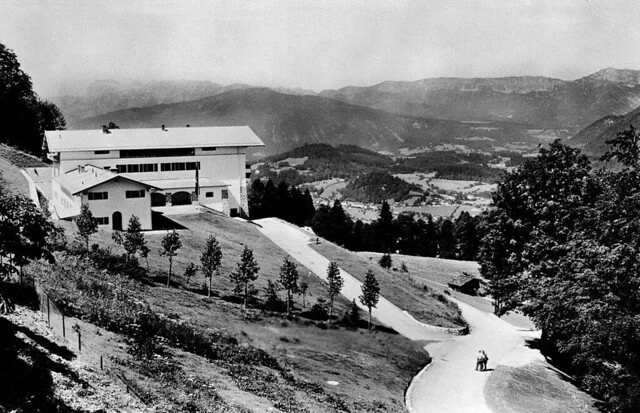

July 20, 1944, Wolfsschanze

Operation Valkyrie conspirators were running out of time. If they hoped to assassinate Hitler and mount a military coup, they had to act quickly.

Despite fierce fighting, Allied troops continued to gain ground in the summer of 1944. On the Eastern Front, Soviet Army tanks crossed the Bug River and entered Poland. British and Canadian forces launched Operation Goodwood, demolished the Germans’ 352 Division, and drove the Wehrmacht out of south Caen, France. Then, on July 17, an American fighter strafed the car carrying “Desert Fox” Erwin Rommel and sent him to the hospital with a head wound.

On the home front, the German Resistance was collapsing. Berlin police issued a warrant for the arrest of one of the top organizers of Operation Valkyrie—Carl Goerdeler—and rumors were swirling about the overall plan itself: Claus von Stauffenberg heard from a German naval officer that people were telegraphing details about an assault on the Führer, saying openly that an attack at Hitler’s headquarters in Wolfsschanze was imminent. (Nigel Jones: Countdown to Valkyrie, Frontline Books, 2008)

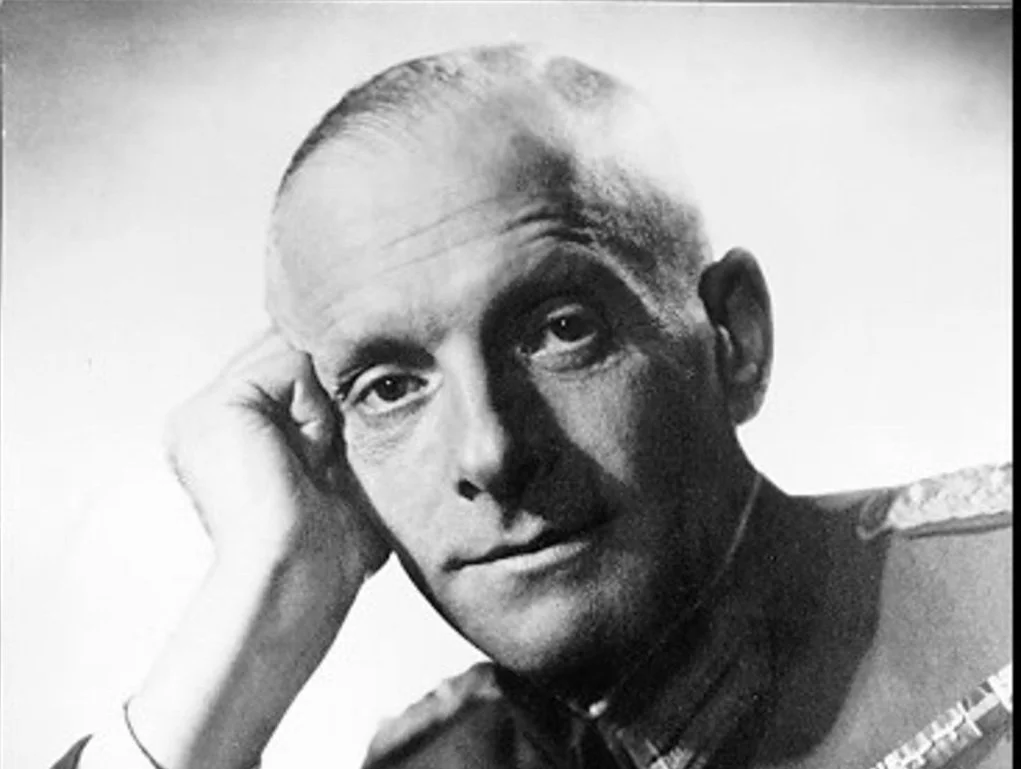

Stauffenbeg and others decided they had to make their move. They decided to take the final, definitive steps of their plan on July 20 at a hastily called conference by the German High Command to discuss the critical situation on the Eastern Front.

https://gazettereview.com/five-human-skeletons-found-outside-home-of-nazi-leader-hermann-goring/

Stauffenberg, fellow conspirator and Reserve Army officer Werner von Haeften, explosives expert Hellmuth Stieff, and an aide flew to Wolfsschanze early that morning. At 11:30 am, Stauffenberg and Haeften were driven through the security zones on the outskirts of the complex into the highly fortified and guarded inner zone, Sperrkreis 1, each cradling a briefcase with two pounds of plastic hexite explosives imbedded with 30-minute fuses.

When the meeting was delayed a half hour to prepare to host Benito Mussolini, Stauffenberg took advantage of the opportunity to work with Haeften, check on the explosives, and trigger the timers so he asked to be taken to a room where he could freshen up and change his shirt.

As soon as they were behind a closed door, Stauffenberg and Haeften set about arming the explosives. From his uniform pocket, Stauffenberg removed a specially prepared pair of pliers (one of the handles had been bent so Stauffenberg could manipulate it with his remaining three fingers). He removed the fuses from one of the bombs and squeezed the copper casings to break the glass vials and release acid into the cotton that surrounded the wiring. He looked through an inspection hole to be sure the spring of the striker pin was intact, removed a safety bolt, and reinserted the fuses. Before he had a chance to arm the second explosive device, the door to the room opened. One man, sent to urge Stauffenberg to hurry along to the conference, called from the doorway: “Stauffenberg, do come along.” Another stood in the doorway, watching the two men as they hurriedly snapped the flaps of their briefcases closed, turned, rushed into the hallway, and went separate ways.

Carrying the briefcase with the unarmed explosive, Haeften left the building so he could be sure a car was waiting to take him and Stauffenberg to the airfield as soon as the trap was set.

Struggling with the weight of the other, armed briefcase under his arm, Stauffenberg started walking to the conference room. When an aide offered to carry the briefcase and placed his hand on the handle, Stauffenberg yanked it away from him. Worried his action appeared to be suspicious, Stauffenberg quickly relented, let the aide carry the briefcase, and asked the man to be sure to place it on the floor under the conference table where he would be standing—as close as possible to Hitler so his impaired hearing would not interfere and he would hear everything the Führer had to say.

The Conference Room

Stauffenberg and the aide entered the conference room at about 12:35 pm. By then, 25 men were standing around a heavy wooden conference table, listening to Major-General Heusinger, acting Chief of the German Army General Staff, provide an update on the Soviet Army’s progress along the Eastern Front and trace troop movements across a map of Russia, Poland, and Germany.

After he was introduced to the group, Stauffenberg approached the right side and corner of the table, just to the side of the trestle that supported it. He then moved close to Hitler so he could shake his hand as the aide placed the briefcase on the floor in front of him.

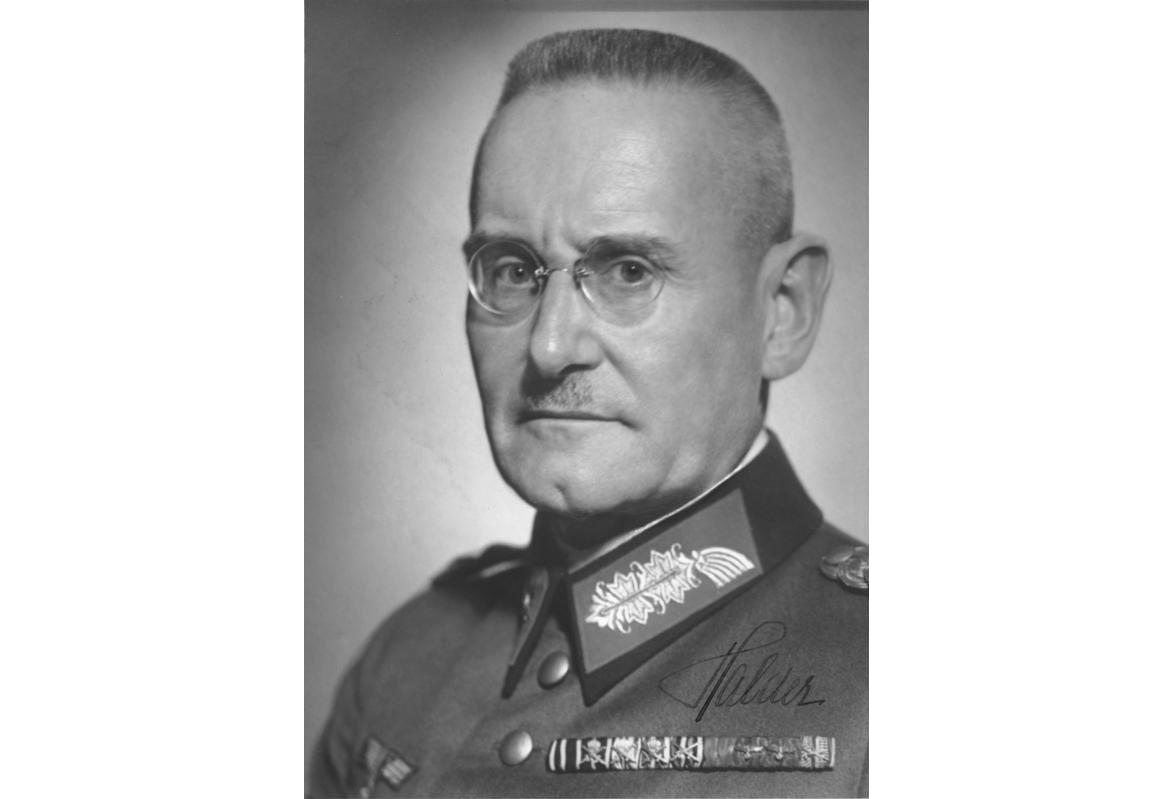

While Heusinger was detailing the desperate position of German troops near Lemberg, Ukraine, Stauffenberg stepped back from the table, whispered to Field Marshall Wilhelm Keitel standing to Hitler’s left that he had to make an urgent call to Berlin to find out the latest information about the Army Reserve units that might be deployed to the Russian campaign.

In the briefing hut moments later, Stauffenberg asked to be connected to the Chief Signal Officer of the Army High Command (and a fellow conspirator), and waited, holding the telephone receiver, until the escort left. As soon as he was alone, he exited the building, and hurried to meet two associates. While the three men were talking, they heard a deafening roar, saw a cloud of smoke and dust rising from the hut, and watched as a body bearing the Führer’s cloak was carried from the building.

Stauffenberg and Haeften climbed into their automobile and drove to the first checkpoint, arriving and passing through the guarded gate at 12:44 pm, about a minute after the explosion. They were stopped at the second checkpoint when an alarm sounded throughout the complex. Stalled behind a barrier and the anti-tank guns and barbed-wire surrounding the airfield, Stauffenberg told guards they must let him and his aide through: he had come directly from the Führer, he said, and had to fly to Berlin at once where a high-level army officer was waiting to meet him. But the sergeant in command refused.

Stauffenberg insisted that the sergeant call Wolfsschanze headquarters so he could speak with an adjutant, Cpt. Leonhard von Mollendorf. Stauffenberg insisted to Mollendorf that the Wolfsschanze commander had given him permission to leave the complex immediately. Although Mollendorf could not verify Stauffenberg’s story, he nevertheless allowed passage, reasoning that Stauffenberg was a valued intelligence officer. He had been to Wolfsschanze many times before and had been honored as a severely injured war veteran.

Thus, the barrier was raised, and the car was allowed to pass. As soon as the auto was far enough away from the barrier, Haeften pulled apart the elements of the second bomb and threw them into the woods. The two men boarded the aircraft and took off at 1:15 pm.

The Explosion

After Stauffenberg left the conference room, one of the officers moved closer to Hitler so he could get a better view of the map and kicked over Stauffenberg’s briefcase. When he bent down to right it, he pushed it further under the table and next to the heavy wooden table support.

As Heusinger was describing the progress of the Russian forces north toward Dvinsk, Adolf Hitler leaned over the table to find the locale on the map. All of a sudden, he was blinded by an intense flash of light and deafened by a heavy, deep roar, then “bluish-yellow flame shot out of the windows, hurling with it glass and splinters, and a cloud of choking black smoke.” (John Grehan: The Hitler Assassinations, p. 188).

One of the generals later reported: “In a flash the map room became a scene of stampede and destruction. At one moment…a set of men…a focal point of world events; at the next there was nothing but wounded men groaning, the acrid smell of burning; and charred fragments of maps and papers fluttering in the wind….” (Countdown, p 192)

Another: “…I saw around me a ruin of wood and glass…At the door a terrible scene greeted me. Severely injured officers lay around on the floor, others were reeling around and falling over.” (The Hitler Assassinations, p 189)

https://www.dhm.de/veranstaltung/zu-spaet-das-attentat-vom-20-juli-1944-auf-adolf-hitler-1/

The heavy 30-foot-long conference table had been blown into three pieces. Pieces of the concrete-reinforced roof had crashed to the floor. Men stood with clothes shredded or burned into their bodies.

And the Führer? “His hair had been set alight; right arm and leg burned and partially paralysed through shock; his black trousers were trailing around his blooded, splinter-flecked legs in tattered ribbons; and both his ear-drums had burst. His buttocks, as he ruefully jested later, had been bruised ‘as blue as a baboon’s behind’ by the impact of him being flung headlong on the floor by the blast.’ (Countdown, p 193)

The body that Stauffenberg and Haeften had seen after the explosion? He was convinced, and he continued telling fellow conspirators as many as five hours later, that Hitler was most assuredly dead, that he had seen Hitler’s dead body. But at the time of the blast, he most likely was too far away to have seen anyone clearly.

Sources

John Grehan: The Hitler Assassination Attempts, Frontline Books, 2022.

Peter Hoffman: Stauffenberg: A Family History, 1905-1944, University of Cambridge Press, 1992.

Nigel Jones: Countdown to Valkyrie, Frontline Books, 2008.

Anthony Shaw: World War II Day by Day, Chartwell Books, 2011.

Eberhard Zeller: The Flame of Freedom, University of Miami Press, 1963.